Introduction

Pesticides are administered to woods, rangeland, aquatic habitats, farming, rights-of-way, urban turf, and gardens in a variety of ways using multiple delivery systems. Because of its widespread use, some species will unavoidably come into touch with pesticide residues. Pesticide poisoning in an ecosystem can occur as a result of either acute or chronic exposure to pesticides. Pesticides may also have a consequence on an ecosystem through secondary exposure or indirect impacts on the animal or its habitat.

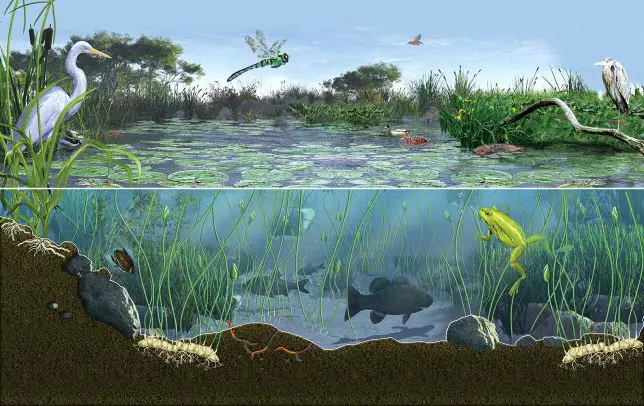

Ecosystems are made up of a mix of living and nonliving organisms, as well as nonliving elements like water, sunlight, and rock. Animals are vital to the establishment and maintenance of the ecosystems in which they dwell. One ecological job of animals in their surroundings, for example, is to behave as consumers, which is an important aspect of the ecosystem’s community dynamics and energy flows.

Because every organism is a member of the food chain/food web/environment, even small species are significant in an ecosystem. Every single animal in the ecosystem plays an important role in the planet’s health. If one species goes extinct as a result of an imbalance, it can have far-reaching consequences throughout the ecosystem.

Acute poisoning

Some pesticides can kill or sicken wildlife after only a few minutes of exposure. Fish deaths caused by pesticide residues conveyed to ponds, streams, or rivers by surface runoff or spray drift, and bird die-offs induced by feasting on pesticide-treated plants or insects, or by eating of pesticide-treated granules, baits, or seeds are examples of acute wildlife poisoning.

Poisonings of this nature can usually be proven by examining the tissues of affected animals for the suspected pesticide or looking into the effects on biochemical systems (e.g., cholinesterase levels in the blood and brain tissue).

Acute poisoning of animals, in general, occurs over a short period of time, affects a small geographic area, and is tied to a single pesticide.

Chronic poisoning

Chronic poisoning can occur when wildlife is exposed to pesticides at levels that are not immediately fatal. The effect of the organochlorine insecticide DDT (through the metabolite DDE) on reproduction in certain birds of prey is the most well-known example of a chronic effect in wildlife. Chronic exposure to DDT and other organochlorine pesticides such as dieldrin, endrin, and chlordane has been linked to birds death.

The reduction of these compounds in the 1970s and early 1980s resulted in lower organochlorine residues in most locations, as well as increased reproduction in birds like the bald eagle. Pesticides containing organochlorines that are used in some foreign nations may endanger migratory birds that overwinter there.

Secondary poisoning

Pesticides can cause secondary poisoning in an ecosystem if an animal eats prey that contains pesticide residues.

Birds of prey becoming sick after eating on an animal that is dead or dying from acute pesticide exposure. The buildup and transportation of persistent chemicals in wildlife food chains are examples of secondary poisoning.

indirect effects

Other than direct or secondary poisoning, a pesticide can have an impact on an ecosystem. When a section of an ecosystem’s habitat or food source is altered, pesticides may have an indirect impact. Herbicides, for example, may reduce insect, bird, and animal populations’ need for food, cover. Nesting locations, insecticides may lower insect populations fed on by bird or fish species.

Insect pollinators may be reduced, influencing plant pollination. The study of indirect impacts is a new field that can be challenging to examine.